Andrew Eagle: By the half-light of a kerosene lamp an old man would recite, in the evenings and some decades ago, the memories of Feni captured in his putipora rhymes. His regular station was on the bank of the Bijoy Singh Dighee, the large pond built in 1760 that occupies 37.75 acres near Feni town.

Chillies on offer, Feni Bazaar.

In verse he would tell of the Bholbhola River, of a warrior’s wife and a boatman’s song. According to him, warrior Bijoy Singh and his wife lived not far from the banks of the fast flowing Bholbhola; and his wife would bathe at its edges. But one day when Singh arrived home to hear his wife was at the river, he also heard a nagging, worrisome boatman’s song wafting in the air like a warning. It was the song, the old man’s verses told, that inspired Singh to block the Bholbhola and build the dighee, so his wife could bathe in privacy, away from the temptation of a boatman’s serenade.

There are other tales – some say a newlywed wife once passed by in a palki or sedan chair when she decided to drink. She was snatched by a bhoot, a spirit, as she drank and dragged into the dighee, never to be seen again. Others say, perhaps it’s related, that from the dighee people took mysterious gold plates and magnificent glasses that emerged from its depths. The dighee facts-cum-legends must’ve been more than sufficient muse for the old man’s rhymes.

Feni is outstanding for its bustle.

Nowadays the dighee is the perfection of a picnic spot: on a windless afternoon it’s a snapshot of the sky to dive into. Apart from fishing enthusiasts and friends hanging out, frequenting the chotpoti snack stalls, there are couples under young love’s spell, trying to be discrete, whose parents may not entirely know where they are.

Values are changing: it’s undeniable. In history’s midst there’s a lot of future in Feni.

Making the most of its strategic location in the Dhaka – Chittagong transport corridor, Feni is outstanding for its bustle. Feni bazaar brims with customers in search of anything from dried fish to gold jewellery, and with at least one in every family working overseas, by local estimate, there’s foreign remittance to drive demand. Feni presents itself as a town eager to acquire all the facilities of Dhaka or Chittagong, with expectations enhanced by those returning from abroad.

Yet in the honk and hassle of its traffic, over those larger cities Feni maintains advantages. It is yet small enough for rickshaws to be practical and with the rumble-trucks and hurtling-buses plying the capital to port city route diverted onto a bypass, of the through traffic Feni is spared.

A shutki (dried fish) shop in Feni Bazaar.

But it’s not because of Feni’s vibrancy that the bypass should be bypassed. Strangely it is that in the arms of a fast approaching future the past so often takes shelter.

In public pond neighbourhoods a smaller Feni can be imagined. In streets where households may yet maintain cattle, where the jewel of Bangladeshi hospitality has not left its shine, village living combines with town lifestyle.

The evening atmosphere of Feni Bazaar is similarly sublime. As the last alleyway-wedged lorry is unloaded, goods heaved hand-to-hand and hauled off on trolleys, the soft glow of bulb replaces the day’s crowds. A shopkeeper is making entries in a hand-bound ledger while a shutki dried fish seller adds to that unmistakable shutki stench the smoke-sweet fragrance of incense, performing his blessing ritual. As the lights go out, with the pounding steps of the last to leave, Feni Bazaar feels intriguingly Dickensian.

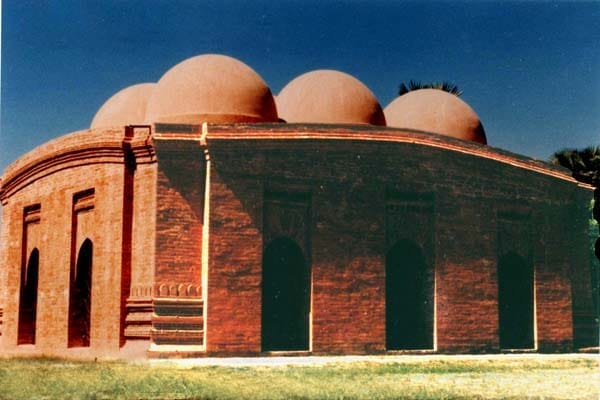

Yet it seems unlikely Dickens would’ve understood Feni, with its long association with the Kingdom of Tippera, the heartland of which is the modern state of Tripura across the nearby Indian border. There’s Tippera’s hint in the Bijoy Singh, and in the central Rajajhee Dighee: the dighee digging tradition features in Tripura’s Udaipur, the traditional capital of the former realm.

In February 1935, the last ruling maharaja His Highness Bir Bikram Kishore Manikya Bahadur Debbarma paid an official visit. “After a drive through the Feni bazaar which was… crowded and decorated with arches, flags and festoons,” it is written of the tour, “His Highness went to attend an Afternoon Party… at which all sections of the public were widely represented.”1 The bazaar must’ve been of special interest since, first called Birendragonj, it was founded by the king. On 16 February 1935 he left by train for his Agartala palace.

Pagla Miah Mazar is the shrine of Sufi ascetic Shah Sufi Amiruddin who died in 1886.

A goldsmith’s display in Feni Bazaar.

Feni Girls’ Cadet college is one of only three girls cadet colleges in Bangladesh.

Abdus Sattar recalls the Japanese bombing raid on Feni, on the last Thursday of March, 1945.

But the king was a figurehead – from 1733 Mughal rule had attained dominance. During the British period ‘Hill Tippera’ became an independent princely state, and in 1947 the plains was slated for inclusion in East Pakistan while the hills joined India in 1949.

Yet the founding of modern Feni town in 1876 is accredited not to Tripuran royalty but to Deputy Magistrate and author Nobin Chandra Sen.

As for the bazaar, it was gradually expanded but later fell into decline. In the lean years it was reduced to a single straw shack by the trunk road where Hindu pilgrims en-route to Sitakunda stopped for supplies of ghur, chira and muri, unrefined sugar, flattened and puffed rice.

Hectic Feni tends to overwhelm the image of Sen’s small town; but there are some who recall a time of even greater urgency.

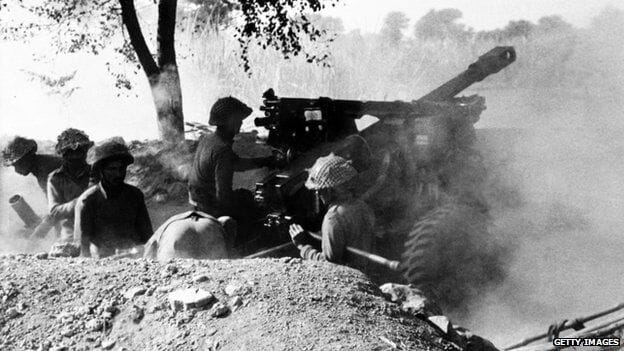

“when the siren sounded everyone would run to the trenches,” recalls 87-year-old Haji Sirajul Haque, whose father worked for the Tripuran king during the Second World War years. Haque was 19 when the war ended and had his own flour business.

When Japanese planes set out from Burma for bombing raids over Feni they were spotted on Allied radar and a pulsating air raid siren would sound. “They were handheld sirens,” Haque says, “It took a good deal of energy to turn the handles – only the strong were asked to do it.”

The many trenches around Feni were dug in the usual zigzag pattern to minimise casualties if a bomb fell into a trench; people waited inside until a single long siren signalled the all clear. “At night in winter we’d sometimes go to the dry canals instead and sleep,” remembers Haque.

“Once, at the sound of the first siren we came home,” says Abdus Sattar, now 85, whose father ran a shop, “but at the second siren, with my father I left by bicycle to go somewhere. We didn’t get far before another siren sounded and we went home again, but after some time the all-clear came so we left for a second time. When we went out we saw a plane overhead. We took our meal at Takea Road and were sitting on onion sacks in the shop when gunfire in the air broke out. We saw smoke.”

Feni was an attractive target. One of several Allied airfields in what is now Bangladeshi territory was constructed there. From Feni airfield, Allied bombing raids were conducted into Burma.

“The Japanese thought if they captured Feni airport,” hypothesises 82-year-old Mohammed Ibrahim, former proprietor of a successful battery business, “it would be a great advantage.”

But following Rangoon’s capture on March 8 1942 the situation was critical for the Allies. Although Japan’s initial goal for the Burma campaign had been to cut supply lines to China, it brought the front line to India’s doorstep. From late 1942 the Allies launched unsuccessful campaigns to halt the Japanese advance. From 1944 the Japanese invasion of India was underway.

Ibrahim lived five miles outside Feni but would accompany his father, who worked at the courthouse, into town. The troops came from several nationalities: “Pathan, Punjabi, Baluchi, Nepali, Gurkha, Indian, British and African. The Nepalis were short, the Africans very strong. Occasionally they gave us biscuits.”

“It was the first time I saw Gurkha and Sikh people,” says Begum Masuda Khatun, 80, “and also frozen fish.”

Abdus Sattar remembers viewing the first plane to land at the airfield. The runway was initially of gravel and the plane broke a wheel on landing. All the children wanted to see it. For them, the sporadic bombing and military activity were exciting.

For the adults too the war brought only moderate change to daily routine. Although Sattar’s family once left for a neighbouring district for two months, for the remainder of the period his father’s shop was open.

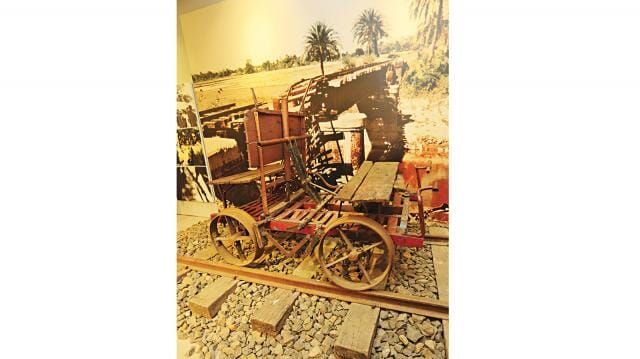

The ‘lal ghar’ from WW2, in Feni Girls’ Cadet College.

Although the price of rice grain rose, according to Ibrahim from 6 poisa per sher, which is a little over a kilogram, to 10 poisa and 3 annas per sher, it didn’t take a large income to cover daily expenses. “Money was valuable,” says Haque, “A day labourer could buy a big chanda fish – expensive now.”

Money itself was, however, in short supply and the military started printing its own. “There was a Punjabi with a machine at the airport,” recalls Ibrahim, “He would push in paper and handmade ten-rupee notes would come out. A Pathan made five-rupee and a Nepali, two-rupee notes. People were paid with handmade money.”

Despite the small-scale bombing raids Feni seemed to have escaped the worst, until that fateful market day, the last Thursday in March, 1945.

“There was loud bombing. It was a big incident,” says Sattar, “I saw planes overhead and people running. I saw boys near the Academy School, their bodies badly burnt.”

“I lay in the canal like soldiers do, taking cover,” says Haque, “Bombs fell inside the Aliya Madrassa, behind and in the dighee. It was around noon. The Japanese planes were white and flew in stork-like formation. A few soldiers died. People died.”

“About 25 – 30 planes attacked,” says Ibrahim, “One pilot parachuted down – she was a woman. There was an unexploded bomb in the mud – they fenced it and for ten years people couldn’t walk there.”

“It was published that 27 planes were shot down,” recalls Khatun, “People said it was actually 14. The soldiers’ bodies were buried in Comilla.”

“That was the last time,” says Sattar, “The Japanese never came again.”

“By mid-1947 all soldiers were withdrawn,” remembers Ibrahim, “By plane they dropped leaflets explaining how the airport land would be divided, which part was for people, which for the government.”

When hurtling along the Dhaka-Chittagong highway, it’s hardly history that comes to mind. But exactly beside the road is what looks like a discarded concrete slab, at road height. On inspection, it’s a half-buried bunker.

Similarly for the train traveller… two bunkers, one in tact, the second with a gaping Japanese bomb hole in its roof are right beside the tracks in the village locally known as Bangaqila, after the broken bunker.

At the centre of the airfield site you can see paving just below the grass, with smaller hangar sites and concrete taxiways in rice paddy country. Then there is the 49.5 acres of former airfield that in 2006 became the Feni Girls’ Cadet College.

Principal Md Mokhlesur Rahman is attempting to plant mango saplings, to add greenery to the college campus of the future, but he faces a problem – there are not less than three layers of runway bricks to remove before finding clear earth.

Responsible for 327 cadets studying from classes 7 – 12 and a faculty of 35 teachers including one Adjutant, Lieutenant Commander Imtiaz Sabir from the Bangladesh Navy, Rahman has a lot to be proud of. Academically the students excel, with the college in first position in the Comilla Board for the last HSC examination when all 46 candidates achieved a GPA 5. It’s not for the first time: outstanding results have become a habit.

Granting time to conduct a tour of the college, we see the modern facilities and an under-construction map-of-Bangladesh feature, somehow appropriate for a college which aims to nurture leadership. In many places the criss-cross brickwork of the old runway is visible and there remains a singular building from the war, once the site office of the Military Engineer Service. It’s simply called the lal ghar, the red house.

I am introduced to the Year 12 prefects, who march into the auditorium and stand while Lieutenant Commander Sabir and I sit, for a chat. I feel sorry for them having to stand.

For Cultural Prefect Anika Tasmia Sejuti, from Patuakhali, the highlight of the college experience is the friendly atmosphere between students and staff. They have additional prep periods, she explains, where teachers are able to fix any problems.

Nafiza Mahzabin, the College Games Prefect from Gazipur, meanwhile, values the opportunity to participate in sports. There’s even a cricket team. “At home girls don’t get the chance to do these things,” she says.

I wonder about the food, and Sadia Khaleque Rochee from Mymensingh is the one to ask. She is the prefect responsible for the dining hall. Every three months a meeting is held, she explains, to design the menu. It must adhere to designated nutritional, calorie and budgetary requirements, but with that is the flexibility to incorporate cadet preferences. Complaints are “mainly about the eggs,” she says, “but there have to be eggs with breakfast.”

The dining hall also presents one of the hardest adjustments to be made on admission, Sadia suggests – learning how to eat with fork and spoon without making sound. “Nobody has any training,” she says, “at home we use our hands.” But within a few weeks the chinks between fork and plate reduce, helped along by the table seating plan whereby older and newer students are assigned to sit together.

By contrast, for House Prefect Farah Naz from Chittagong, it was the physical training that was most challenging. “There aren’t many girls habituated to exercise,” she says. The cadets complete half an hour of exercise each morning and an hour of sport each afternoon.

But Farah remembers her first day fondly – a class 8 student was assigned to help her arrange her locker, bed and table, and to explain the regulations, including how to behaviour with seniors. Moreover the day was special because she arrived with her television-actor-uncle and other cadets were jumping around him to collect his autograph. “People were very interested to see me, his niece,” she remembers.

Chittagonian Mayisha Nur has been inspired by her experience as a House Prefect, she explains, to pursue a career in politics. “It taught me how to make decisions,” she says, “and there is a lack of leadership in Bangladesh.” Her initial hopes are to reform the admissions system so that Bangladeshis can more easily realise their potential, and to confront public corruption. She aims high. “Ultimately I will be, insha’allah, Prime Minister,” she says.

Of course the Prime Minister’s job is not easy. “We can all have problems, times when we need a psychiatrist,” says Sadia, indicating her intended career. She agrees that even a future Prime Minister might need her help one day.

On campus they are constructing a new map of Bangladesh. The Principal is at pains to dig through airfield bricks to plant mango trees – in every future the past takes shelter. But there’s a lot of future in Feni.

1) Mahadev Chakravarti (ed.), Administrative Report of Tripura State since 1902, Gyan Publishing House, 1994, Vol. 4, p.1743

***

TOWARDS A BETTER FENI

Beyond the Sonagazi Weir in Feni district three unused windmills add feature to the landscape of the tidal zone. There, the wild lawn served easily as football pitch for town dwellers. Meanwhile, at the lake on the nearer side was swimming and boating.

The 2011 winter picnic of Feni’s Oboshor or Leisure Club, was a lucky day. I won second prize in the raffle – dinner plates. It was the best result since first prize was a live goat!

Stretching back to the British era, the culture of clubs is well-established in South Asia. Clubs can be status-oriented and expensive; Oboshor is different.

“Our society suffers from a cancer,” Oboshor’s Vice-President Mominul Hoque wrote in the club’s publication, “We never learnt to admit our faults. People like to boast. We wanted Oboshor members to believe in taking responsibility for mistakes.” Oboshor is non-political, committed to Feni and a belief that all are equal.

The club originated several years ago in a broken, straw house, a kupri ghar, in Feni bazaar. Initially friends used to gather for adda. In the course of daily conversations, horizons grew.

With the decision to formalise into a club, larger premises were sought and current president, Alal Uddin Alal, offered the rooftop of his unfinished commercial building. To this day reaching the clubhouse involves negotiating a construction site’s dark stairwell. It can’t be imagined Oboshor is up there.

Meanwhile, the club’s aspirations took shape. “We wanted to make a better society,” Mominul Hoque explained. To this end, Oboshor created the Nobin Chandra Sen education scholarship, with the hope that if even one of its recipients should succeed the project will have been worthwhile.

Each winter the club donates warm clothes to the needy and has presented sewing machines and rickshaws to struggling families. But the club is also about having fun.

I didn’t know much of this when I was offered the chance to join. “How much does it cost?” I asked.

“It’s free,” the club president said.

“What are the criteria?”

“Just one: good character.”

Collected from The Daily Star

***ফেনী অনলাইন সংক্রান্ত যে কোন তথ্য ও আপডেট জানতে জয়েন করুন আমাদের ফেসবুক গ্রুপে।***

@FeniOnline

@FeniOnline

লিংক -

লিংক -

Comments